Rapid Adaptation: Redesigning a VA Senior Living Center to Contend with COVID-19

By Jay Pelton, RA, LEED AP, & Morgan Young

In 2019, the Lebanon, PA Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center tapped Miller Remick and Array Architects to design and construct a Community Living Center (CLC) that follows the VA standard small house modelfor their campus. Little did the team know that the pandemic was about to fundamentally change how age-in-place environments are designed. In this article, we’ll review strategies to adapt existing designs to meet new guidelines by exploring how the design team addressed MEP and operational challenges posed by the pandemic.

In 2019, the Lebanon, PA Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center tapped Miller Remick and Array Architects to design and construct a Community Living Center (CLC) that follows the VA standard small house modelfor their campus. Little did the team know that the pandemic was about to fundamentally change how age-in-place environments are designed. In this article, we’ll review strategies to adapt existing designs to meet new guidelines by exploring how the design team addressed MEP and operational challenges posed by the pandemic.

Project Overview

The existing CLC is located inside the 1940s H-shaped historic nine-story inpatient building on the sprawling campus. Each floor plate was only 30-40’ wide, with the structure and double-loaded corridors limiting each resident room to be no more than about 15’ wide.

Phase one of this project consisted of a full master plan to move their current beds into

Phase one of this project consisted of a full master plan to move their current beds into

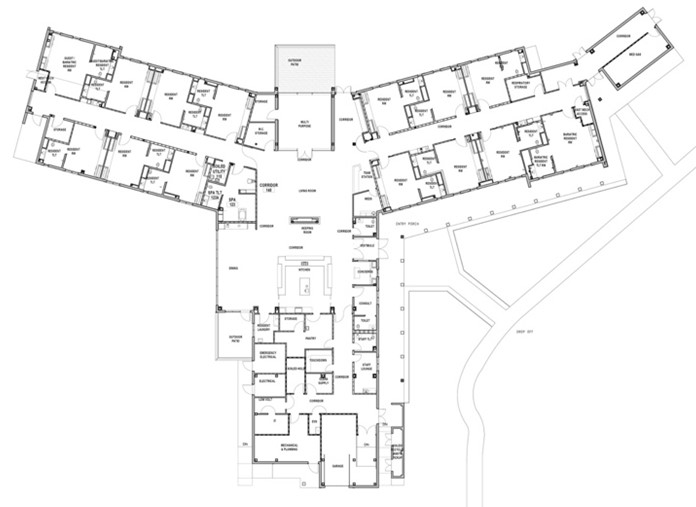

small houses to be constructed on campus. This aligns with the guidance of the new small house model, which includes four 14-resident CLCs and one town/community center which will interconnect all residents. During the master plan, the team determined we would need to relocate 56 beds, so the CLCs evolved into four small house models – all connecting to one central town hub through a series of connecting corridors.

The team had completed the CLC’s schematic design when March 2020 arrived. As the pandemic took hold, the VA remained steadfast in protecting their residents with new HVAC solutions in the inpatient hospital. The VA learned a lot at that time, often acknowledging that sealed shut windows were a very difficult obstacle.

Questions and Downstream Implications

The team began their re-evaluation when the building was at 35 percent completion. At this stage, the building was designed with mechanical and available infrastructure efficiency in mind and was equipped with geothermal heat-pumps and a single air handling unit. Working with the VA, Array and Miller Remick looked at what could be done to improve the residents’ outcomes should the pandemic happen again, after the future CLC was occupied.

The first decision was determining how far to take the protection. Would we need to treat each small house separately? Would we need to treat each connected community differently, or address each individual on a case-by-case basis? Would staff need to don and doff equipment differently? How would the normal course of meals and daily resident life be altered? Would they be able to share in the planned small house amenities?

The team first looked at the plan to determine what would create the most versatile solution. We explored how we could prevent airborne virus spread most effectively. The current VA approach to protecting the veterans inside their hospital rooms naturally influenced our thinking. The team considered this approach within the context of the floorplan layout. If we needed to boost our HVAC system, we had to start over, and knew we had to begin with the level of protection necessary to provide residents and staff protection during a pandemic. Our floorplan was a Y-shaped spine and two wings. Each wing contained seven rooms.

Re-assessing Floor Plans

The team looked at the plan for how to limit airflow among all spaces. Originally, there was only one air handling unit (AHU); the building was designed efficiently with geothermal pumps producing a majority of the conditioning with a lower air delivery. The team determined that if there were COVID-positive residents, one AHU will no longer be sufficient because it would make the whole building ‘hot,’ or contaminated. Our design was now at risk and we needed to determine how to revise the HVAC system. But first, we needed to tackle the transmission problems. We established rules for three categories of residents: those who were in contact with COVID, those who were not and those who might have been. In looking at residents who were, the agreement was to limit room air exposure recirculation.

Working with the VA, we developed a series of options. When we compared an isolation room-type scenario to these air delivery needs, it quickly became evident that these rooms needed to be 100-percent exhausted. Along with the design community at large, we learned that contact tracing would not be able to definitively identify the residents with COVID in time for them to properly isolate. Therefore, we needed to treat everyone who went to their own room as if they had COVID. We also needed to designate safe areas for the staff to continue to support residents, both in and out of the hot zones. Very quickly, we decided to limit the access to the resident corridors with closeable doors from the main spine and treat the rest of the rooms as if they were clean.

Determining New Needs

Now that we identified a layout and compartmentalization strategy that accomodates occupants during a pandemic, the next step was to assess the new needs of the mechanical system. We determined that one geothermal-fed unit would not have sufficient capacity for new air requirements because the air changes per hour (ACH) would go from two to a minimum of six per residential room. In order to redesign the system, the team implemented a plan to provide multiple chilled water air handlers, one for each wing’s distribution, plus a 100 percent exhaust system.

Key Takeaways for Updating HVAC in Age-in-Place Environments

Selecting the right HVAC system for age-in-place environments is important to ensure your facility is future ready. Here are five key takeaways from our experience to guide your decision:

- Select an HVAC system that provides conditioned air by a Variable Air Volume AHU. By doing so, our team was able to provide the VA a “Pandemic-mode” for the resident wings which prevents recirculated air within the building and meets the minimum six ACH per hour.

- Ensure the AHUs are capable of negatively or positively pressurizing each resident’s room to isolate infected patients from the remaining population. In our case, three AHUs – one for the central core/spine, and one each for the two resident wings – were needed.

- Specify for versatility. At the CLC, the HVAC system feeding the residents’ rooms will allow for the rooms to be convertible from normal condition, nearly pressure balanced with respect to the adjacent corridor, to a negative pressure condition. This will be accomplished by increasing the air flow of the supply air valve serving each of the resident rooms so that the rooms will go positive relative to the resident bathroom and the adjacent corridor. Additional back-up of natural ventilation can be achieved through operable sashes in the windows.

- Adopt advanced air purification equipment. For this project, our team used Genesis Air as a basis of design, which utilizes photocatalytic oxidation to reduce infection and improve the indoor environment in hospitals. Data shows that hospitals with this equipment in critical care areas have a significantly lower MRSA standard infection rate.

In Closing

Rapid adaptation is possible to a design-in-progress for an age-in-place environment like this Veterans Affairs Community Living Center. When retrofitting a facility or modifying a design, weigh how the layout can be reconfigured to safely compartmentalize patients as needed, and identify the most critical planning elements that must be addressed. Working in tandem with a skilled MEP firm, select and specify the right HVAC system, one that allows for negative and positive pressurization, appropriate AHUs, versatility and air purification.

Prior to the publication of this article, the FGI offered draft guidancefor designing resilient healthcare and residential facilities to adapt to emergency conditions, including pandemic response.

Downloade the high-reg images found in this article by clicking here.

About the Authors

Jay Pelton, RA, LEED AP

A Principal and Project Architect at Array, Jay Pelton is passionate about delivering projects that offer sustainability, energy efficiency and environmental harmony. His technical focus ensures a proper coordination between building engineering elements, the established building program, and the aesthetic goals of the institution.

Morgan Young

An Architectural Designer at Array Architects, Morgan Young is inspired by the opportunity to drive positive change in people’s lives through the built environment. His experience includes work with clients across the mid-Atlantic, and he has earned awards and co-edited grant publications rlating to his design savvy and expertise.